18 open source translation tools to localize your project

Localization plays a key role in adapting projects for users around the world.

Localization plays a central role in the ability to customize an open source project to suit the needs of users around the world. Besides coding, language translation is one of the main ways people around the world contribute to and engage with open source projects.

There are tools specific to the language services industry (surprised to hear that’s a thing?) that enable a smooth localization process with a high level of quality. Categories that localization tools fall into include:

- Computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools

- Machine translation (MT) engines

- Translation management systems (TMS)

- Terminology management tools

- Localization automation tools

The proprietary versions of these tools can be quite expensive. A single license for SDL Trados Studio (the leading CAT tool) can cost thousands of euros, and even then it is only useful for one individual and the customizations are limited (and psst, they cost more, too). Open source projects looking to localize into many languages and streamline their localization processes will want to look at open source tools to save money and get the flexibility they need with customization. I’ve compiled this high-level survey of many of the open source localization tool projects out there to help you decide what to use.

Computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools

omegat_cat.png

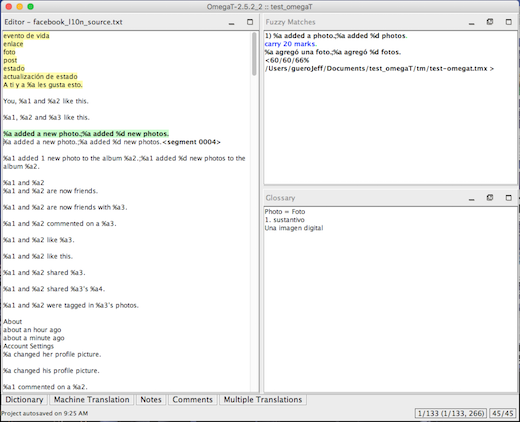

OmegaT CAT tool. Here you see the translation memory (Fuzzy Matches) and terminology recall (Glossary) features at work. OmegaT is licensed under the GNU Public License version 3+.

CAT tools are a staple of the language services industry. As the name implies, CAT tools help translators perform the tasks of translation, bilingual review, and monolingual review as quickly as possible and with the highest possible consistency through reuse of translated content (also known as translation memory). Translation memory and terminology recall are two central features of CAT tools. They enable a translator to reuse previously translated content from old projects in new projects. This allows them to translate a high volume of words in a shorter amount of time while maintaining a high level of quality through terminology and style consistency. This is especially handy for localization, as text in a lot of software and web UIs is often the same across platforms and applications. CAT tools are standalone pieces of software though, requiring translators that use them to work locally and merge to a central repository.

Tools to check out:

Machine translation (MT) engines

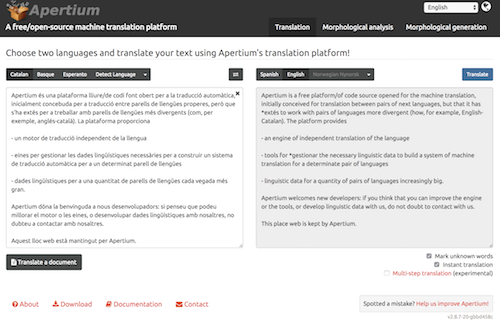

MT engines automate the transfer of text from one language to another. MT is broken up into three primary methodologies: rules-based, statistical, and neural (which is the new player). The most widespread MT methodology is statistical, which (in very brief terms) draws conclusions about the interconnectedness of a pair of languages by running statistical analyses over annotated bilingual corpus data using n-gram models. When a new source language phrase is introduced to the engine for translation, it looks within its analyzed corpus data to find statistically relevant equivalents, which it produces in the target language. MT can be useful as a productivity aid to translators, changing their primary task from translating a source text to a target text to post-editing the MT engine’s target language output. I don’t recommend using raw MT output in localizations, but if your community is trained in the art of post-editing, MT can be a useful tool to help them make large volumes of contributions.

Tools to check out:

Translation management systems (TMS)

mozilla_pontoon.png

Mozilla’s Pontoon translation management system user interface. With WYSIWYG editing, you can translate content in context and simultaneously perform translation and quality assurance. Pontoon is licensed under the BSD 3-clause New or Revised License.

TMS tools are web-based platforms that allow you to manage a localization project and enable translators and reviewers to do what they do best. Most TMS tools aim to automate many manual parts of the localization process by including version control system (VCS) integrations, cloud services integrations, project reporting, as well as the standard translation memory and terminology recall features. These tools are most amenable to community localization or translation projects, as they allow large groups of translators and reviewers to contribute to a project. Some also use a WYSIWYG editor to give translators context for their translations. This added context improves translation accuracy and cuts down on the amount of time a translator has to wait between doing the translation and reviewing the translation within the user interface.

Tools to check out

Terminology management tools

baseterm_term_entry_example.png

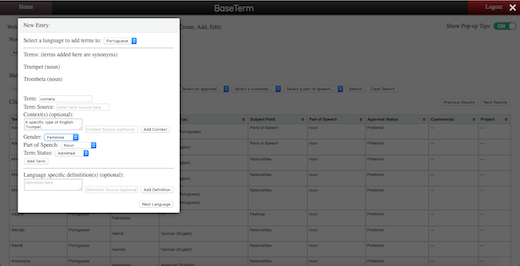

Brigham Young University’s BaseTerm tool displays the new-term entry dialogue window. BaseTerm is licensed under the Eclipse Public License.

Terminology management tools give you a GUI to create terminology resources (known as termbases) to add context and ensure translation consistency. These resources are consumed by CAT tools and TMS platforms to aid translators in the process of translation. For languages in which a term could be either a noun or a verb based on the context, terminology management tools allows you to add metadata for a term that labels its gender, part of speech, monolingual definition, as well as context clues. Terminology management is often an underserved, but no less important, part of the localization process. In both the open source and proprietary ecosystems, there are only a small handful of options available.

Tools to check out

Localization automation tools

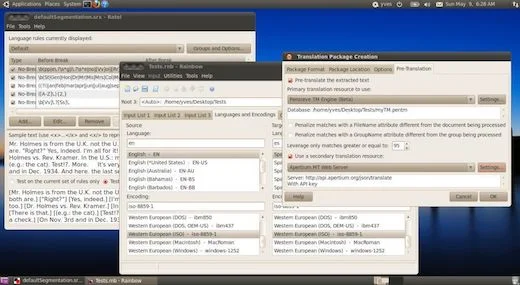

okapi_framework.jpg

The Ratel and Rainbow components of the Okapi Framework. Photo courtesy of the Okapi Framework. The Okapi Framework is licensed under the Apache License version 2.0.

Localization automation tools facilitate the way you process localization data. This can include text extraction, file format conversion, tokenization, VCS synchronization, term extraction, pre-translation, and various quality checks over common localization standard file formats. In some tool suites, like the Okapi Framework, you can create automation pipelines for performing various localization tasks. This can be very useful for a variety of situations, but their main utility is in the time they save by automating many tasks. They can also move you closer to a more continuous localization process.

Tools to check out

Why open source is key

Localization is most powerful and effective when done in the open. These tools should give you and your communities the power to localize your projects into as many languages as humanly possible.

Want to learn more? Check out these additional resources:

Originally published on OPENSOURCE.COM