Are bilinguals better language learners?

It is easy to assume that bilinguals are better at adding another language to their repertoire. But is that always true?

Evidence from English language learning in multilingual classrooms in Europe

School children in European countries such as Germany all study English as a foreign language as part of their education. Most of these school children will be monolingual in German but an increasing number speaks a language other than German at home. How do these students’ monolingual repertoires in German or bilingual repertoires in German and another language affect their learning of English?

This is the question explored by Professor Peter Siemund from Hamburg University in his lecture in the Lectures in Linguistic Diversity series at Macquarie University.

Professor Siemund started out by identifying a paradox of multilingualism research: multilingualism is often thought to be an advantage for both cognitive development and learning, but, at the same time, cross-linguistic influence research shows that speaking more languages often leads to more negative interference in the learning of subsequent languages.

For instance, he cited research (Lorenz, 2018) that found that Turkish and Russian monolingual learners of English were able to get the meaning of the English progressive aspect right 100% of the time. In contrast, German-Turkish and German-Russian bilinguals only got it right about as frequently as monolingual German speakers. It seems obvious that transfer from German, which has no progressive aspect, negatively affected the English language learning of these bilinguals. So in this case, bilingualism did not help but hinder when it came to this particular grammatical feature of English language learning.

Different languages, different findings

In another study described by Professor Siemund the relationship between reading comprehension scores in German and another language on the one hand and test scores in English on the other were examined. It was found that German comprehension skills correlated with English test performance for German-Russian bilinguals but not for German-Turkish bilinguals. This highlights the fact that bilingualism is not a unitary phenomenon and is different depending on which languages are involved.

Accuracy versus flexibility

It is not only bilingualism that is not a unitary phenomenon but the same is true of language learning. What do we mean when we say that someone is a good language learner?

One relevant dimension is linguistic accuracy; another is linguistic fluency. In my own experience as a language learner and teacher, learners who are more accurate are often less fluent, while those who are more fluent often sacrifice accuracy.

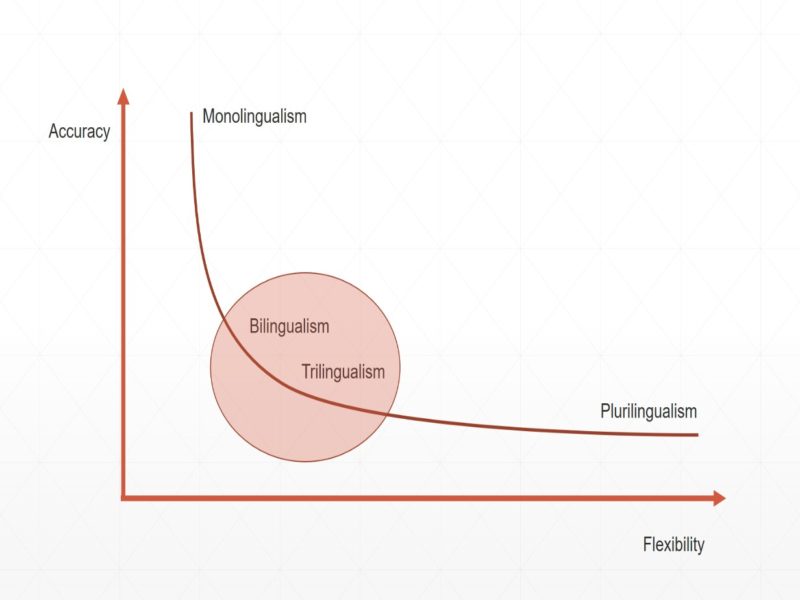

This was also the conclusion reached by Professor Siemund, who argued that there is a trade-off between accuracy and flexibility. While monolinguals might be more accurate, plurilinguals might be more flexible. He closed by suggesting that bi-and trilingualism might be equilibrious points where accuracy and flexibility are most likely to be in balance.

What do these findings mean for advocacy?

For those of us who are interested in advocating for the rights of migrant language speakers, it can be tricky to talk about the disadvantages of being bilingual or multilingual. It is a balancing act between supporting linguistic diversity and fighting against the discrimination experienced by speakers of minority languages. Supporting linguistic diversity in the abstract sometimes overshadows the fact that some kinds of bi/multilingualism are clearly more equal than others. In fact we already know that being multilingual can be disadvantageous in education and at work, whether it’s for minority language-speaking children who are unable to access education in their first language and standardised tests which discriminate against them or migrants whose linguistic repertoires are problematized in the workplace.

Maybe we need to reframe the question: instead of asking what the advantages or disadvantages of bi- and multilingualism might be, we should ask how we can help ensure equality of opportunity regardless of linguistic repertoire, as Ingrid Piller does in her recent book Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice.

References

References

Lorenz, E. (2018). “One day a father and his son going fishing on the Lake”: A study on the use of the progressive aspect of monolingual and bilingual learners of English. In Bonnet, A. and P. Siemund (eds.) Foreign Languages in Multilingual Classrooms (pp. 331–357). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Piller, I. (2016). Linguistic diversity and social justice: an introduction to applied sociolinguistics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

This post was originally published on Languageonthemove.com