MIT Scientists prove adults learn language to fluency nearly as well as children

Scott Chacon is CEO of the online language learning company Chatterbug.

Scott Chacon is CEO of the online language learning company Chatterbug.

This week a new paper was published in the journal Cognition titled “A Critical Period for Second Language Acquisition” that used a new, viral Facebook-quiz-powered method of gathering a huge linguistic dataset to provide new insights into how human beings learn language and what effect age has on that process.

In a nutshell, this team found that if you start learning a language before the age of 18, you have a much better likelihood of obtaining a native-like mastery of the language’s grammar than if you start later. This is a much older age than has been generally assumed and is really interesting for reasons I’ll get into a bit later.

This data has also given us a really amazing insight into language learning in general and shows that adults of any age can obtain incredible mastery nearly as quickly as children.

Unfortunately, a number of journalists have misinterpreted this paper badly, resulting in a lot of articles falsely stating things as embarrassing and misleading as “Becoming fluent in another language as an adult might be impossible”, when in fact the opposite is shown. If you see an article saying that you need to start learning a language before you’re 10 to become fluent, be assured that it’s simply lazy reporting. The truth is much more interesting and encouraging.

We know this, because in an incredible move, the researchers have released the entire dataset they based this paper off of, letting us take a look. Let’s go through some interesting things that this amazing data shows us about learning languages and why it should motivate you to try.

Many late learners become native-like

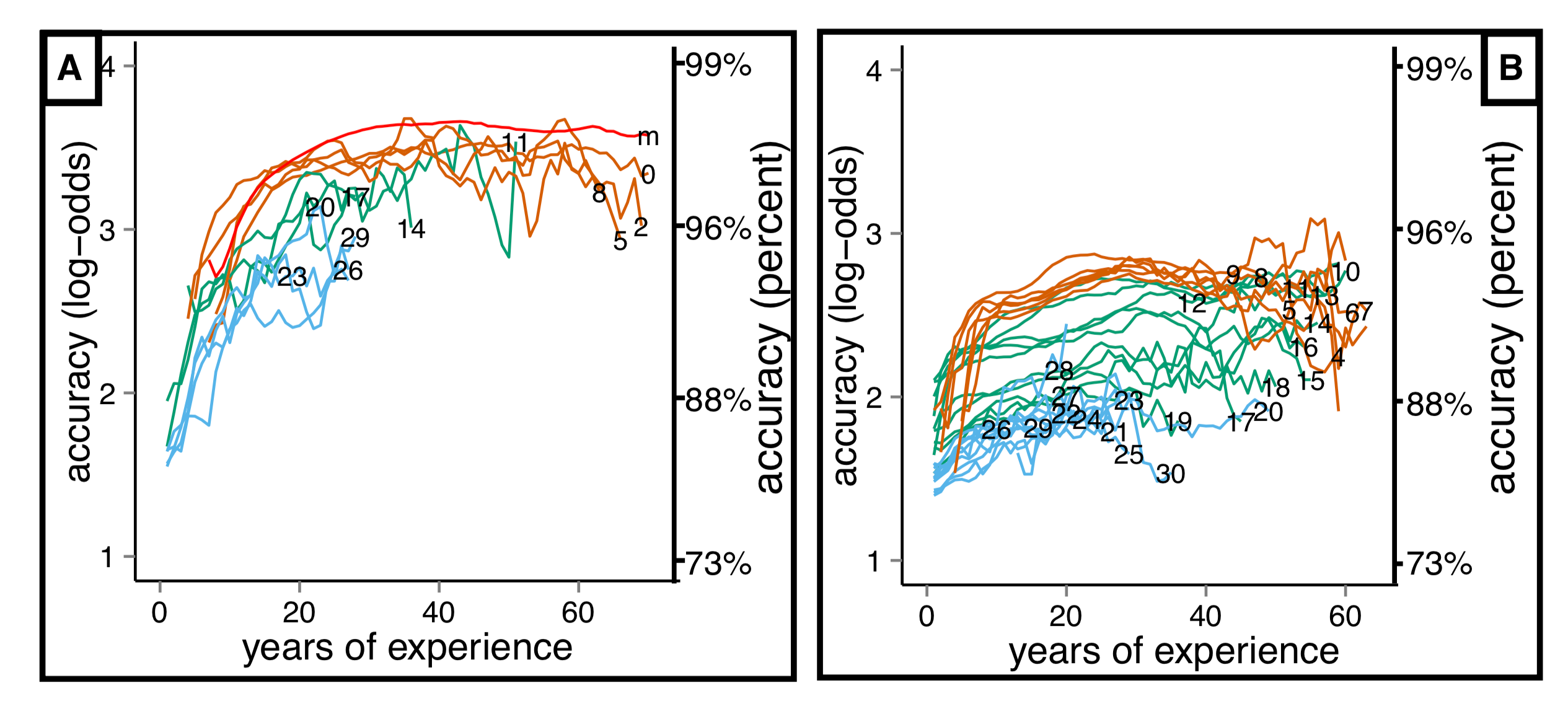

Looking through the data, it’s quite clear that there is a statistical advantage to starting your learning earlier. If you compare the average score of learners who started at different ages, there is a clear advantage to having started earlier.

However, looking more closely at the data for the students who started learning after the age of 20, there are a lot of late learners who outperformed many native English speakers.

First, we need to specify what “native-like” performance on this quiz is. Looking at the quiz results of the group of users who are tagged as native English speakers, we have a range of scores from 100% (which 12% of native speakers scored) down to scoring 90% for the bottom 5% of native speakers. To me, this indicates that scoring anything above a 90% on the test means you’re performing at least as well as many native speakers would.

Many articles have breathlessly stated that it’s just impossible to achieve native-like mastery if you start after the age of 10 (or 18, depending on the article), but is that true? Certainly on average the later learner seems to have a rarer time getting there, but is it impossible?

The data tells us that it’s not. On average less likely, certainly, but there are thousands of people who took this quiz, got a score in the range that a native speaker would, and started learning the language after the age of 20.

Thousands of adults who started learning after 20 years old scored in a native-level range

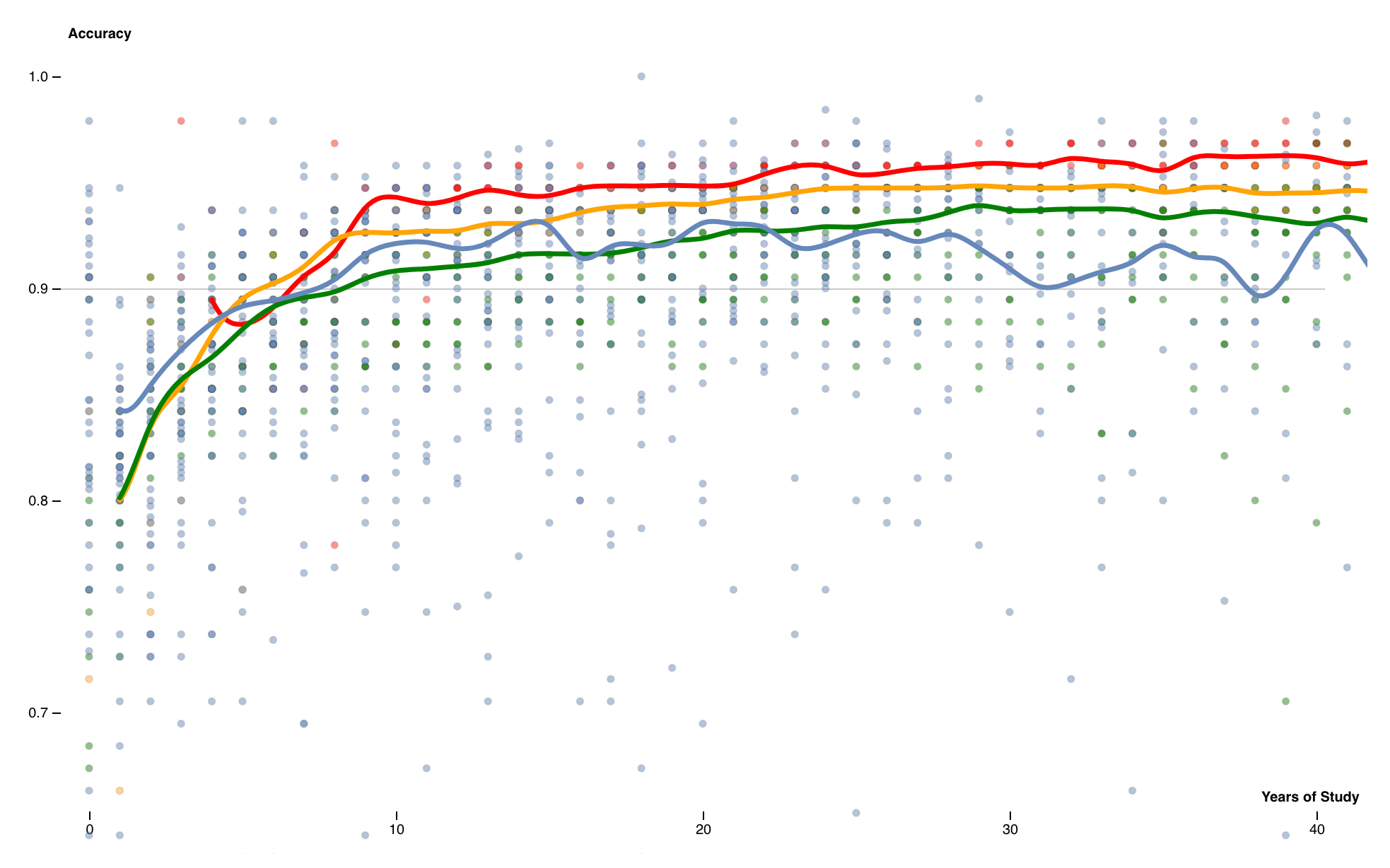

Instead of looking at the median of this late-learning group, let’s just look at the top quartile of the speakers who started learning after the age of 20. We can graph that adjusted by how many years since they started studying the language.

Here we can see that many of the later learners score easily within the range that native speakers do (above the 0.9 line). In fact, if we graph the results of the top quartile of after-20 learners with the median scores of the other groups (those who started learning before 5, before 10 and before 20 years old), it doesn’t look much different.

Given the same amount of time, the top quarter of learners from the over-20 group do just as well as the average of those who started before 10.

(After about 20 years of learning exposure, the over-20 group line gets pretty wobbly, since we have less and less data to work with — starting at 20 and having 20 years of exposure makes the youngest group there at least 40 years old).

Comparing apples to apples

But why would we do this? Shouldn’t we compare the medians of all of the groups, like the very first graph? Shouldn’t we compare apples to apples — it’s not really fair to compare the median of one group with the best of another, right?

Well, the problem is that there is no way to compare apples to apples with this dataset, and the authors point this out.

This is because the “drop” in learning advantage happens at 17 or 18 years old according to this paper, but why is that? What happens at 18 years old? Is it that there is some incredible and magical brain-change that happens? Or is it that people’s lives fundamentally change on average — you go to college, you enter the workforce, you move out of your parents house, etc?

“For instance, it remains possible that the critical period is an epiphenomenon of culture: the age we identified (17–18 years old) coincides with a number of social changes, any of which could diminish one’s ability, opportunity, or willingness to learn a new language. In many cultures, this age marks the transition to the workforce or to professional education, which may diminish opportunities to learn.” — from A Critical Period

If you start “studying” a language at the age of 5, you’re not sitting down with a book and explicitly learning the language for an hour a day. You’re almost certainly in a classroom environment where that language is spoken, possibly for several hours per day. If you start learning a language after you’re 20 years old, you almost certainly cannot be in a classroom for several hours per day.

This brings up a big problem with the interpretation of this data. It gives us a lot of information, but it doesn’t give us the most important thing, which is the total amount of exposure that these students have had. I would argue that on average, your exposure per day to a language if you start after the age of 20 is going to be way lower than if you start when you’re 5.

If you’re in an English speaking school for 5 hours a day as a kid and your parent is studying the same language for an hour a day while you’re there and the kid learns 5 times faster than the parent, is it fair to then conclude that kids learn better than adults?

It’s highly possible that this learning difference by age is not due to some magic change in brain plasticity, but simply that adults don’t have as much time to be exposed as children and often hit a point where it stops being helpful to improve after a while. They become totally fluent at this slower pace and reaching native-level mastery provides little additional advantage. Maybe it’s not that it’s harder for older learners or that they’re not capable, maybe it’s just that they don’t have the same opportunity.

Comparing the top quartile of the post-20 group is a simple guess to isolate a cohort of language learners who may have had more opportunity for exposure. I would guess that the post-20 learners would have much less uniform types of opportunities than children, whose experiences are probably much more similar in nature. It’s certainly not perfect, but it does indicate that there is a cohort in the post-20 crowd that does very well.

This quiz is incredibly hard

There are a couple of other interesting things to note here. The first is how hard this quiz is. Even for the learners who started studying the language as a young child, it takes at least 7–8 years of exposure before any of the groups are consistently scoring above a 90% on this test.

This test is not about fluency, it’s about highly pedantic grammatical accuracy. If you got through this entire test at all, you’re probably pretty close to basic fluency.

If you’re thinking that this paper provides some reason why you’re not fluently speaking French after your 3 months of using some language-game app, you are wrong. Children won’t learn a language masterfully that way either.

“Studies that compare children and adults exposed to comparable material in the lab or during the initial months of an immersion program show that adults perform better, not worse, than children (Huang, 2015; Krashen, Long, & Scarcella, 1979; Snow & Hoefnagel-Höhle, 1978), perhaps because they deploy conscious strategies and transfer what they know about their first language.” — from A Critical Period

Adults are actually better in many ways at learning a language up to a point of general fluency, but getting to where you can answer the most subtle of grammatical points with the accuracy of a native speaker takes a decade no matter how old you are when you start.

That so many adults who started learning a language after 20 years old (or even later) did so well on this test should be encouraging. If you want to put in the effort, it’s entirely possible to perform at a native level on an incredibly difficult test like this — thousands of people did just that.

It doesn’t matter what language you come from

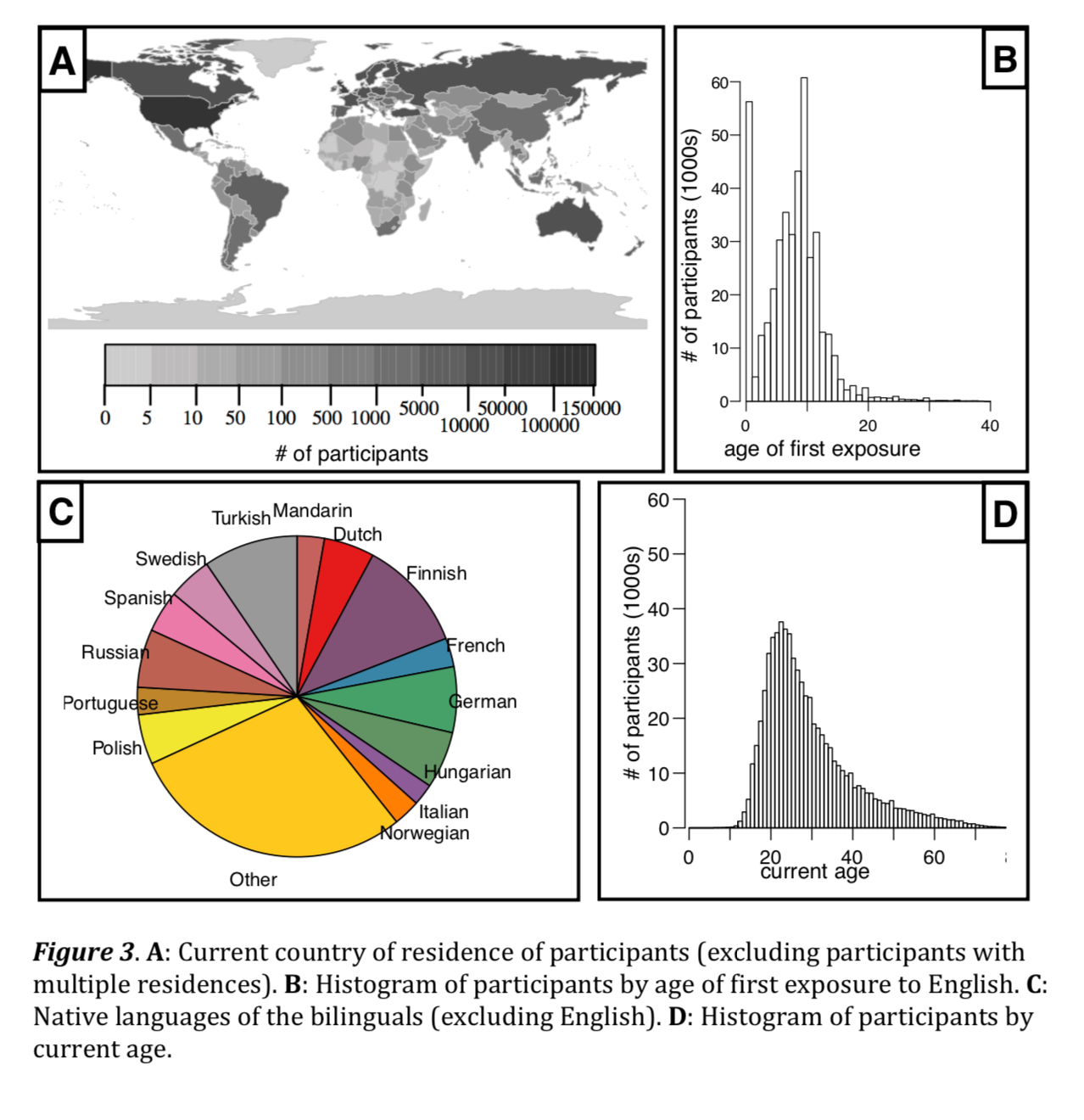

This paper also gives us some really interesting insights from a broad range of backgrounds. They had nearly 3/4 million people take the quiz and got demographic data from everyone.

The first thing to notice is how little data they actually were able to get from people who started after the age of 20. It’s a tiny fraction of their dataset.

The other thing is how many different languages learners came from.

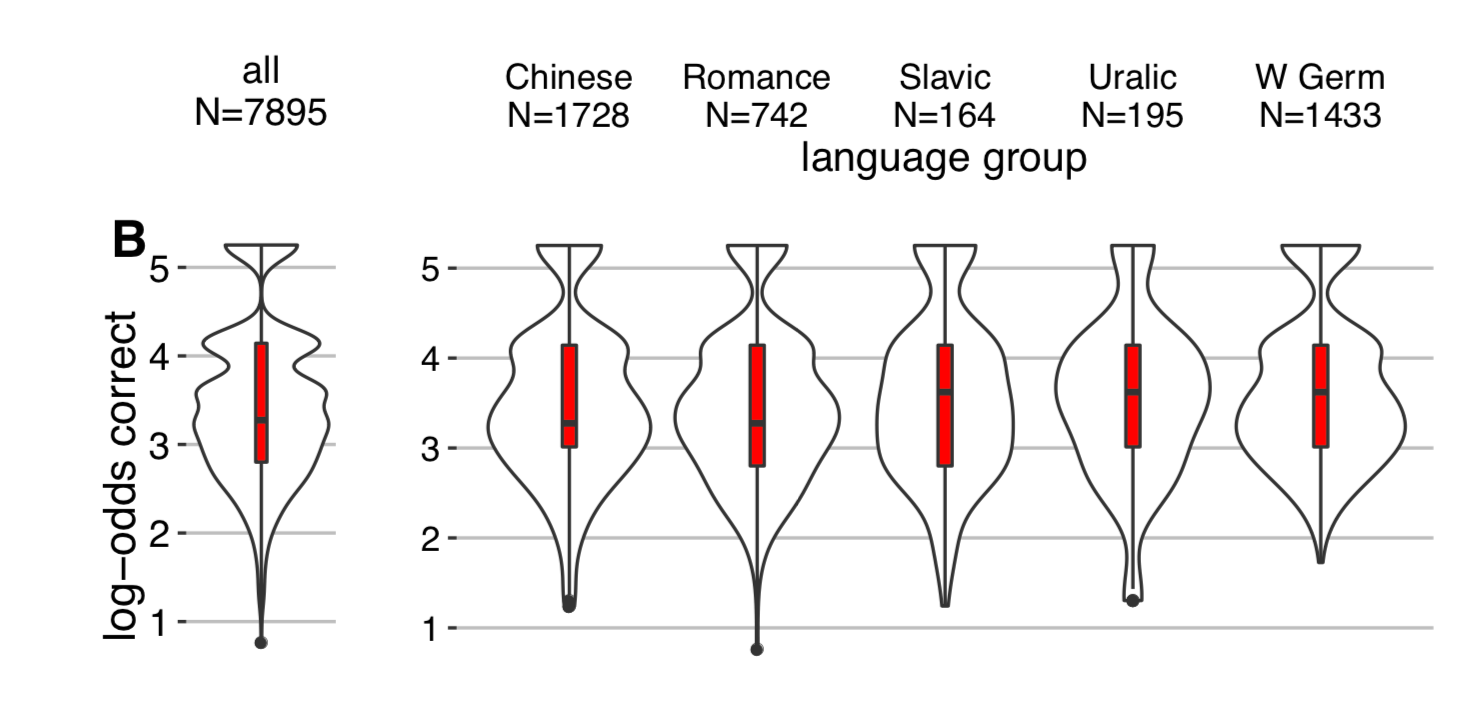

It’s common to say “this language is hard to learn” or “that language is so easy”, but this data showed that these things may not be true. They found that there was little difference in the learning speeds or ultimate attainment of English coming from any linguistic background.

“In fact, the differences across language groups were small (see Fig. S14) and generally not reliable.” — from A Critical Period

Studying a language for a year can make you quite fluent

Finally, the thing I would like everyone to take away from this is how good adults can be at language learning. It may be harder for us to get to where we could pass for a native, but that’s probably pretty obvious and not why most of us start learning a language, right? You’re not trying to be a spy.

Take a look at my previous graph of the various language groups. You can see that even after a year of studying, the 20+ year old start group is commonly scoring 80-85% on this incredibly difficult grammar test.

Sure, it takes another 10 years to get to where you might pass for a native on this test, but look at what you can do in a single year!

Don’t use poorly reported studies like this convince you not to try learning a language. The truth is that you’re almost certainly very good at it. People consistently learn new languages in a year or two from no knowledge to very capable, fluent levels and in my personal experience, much faster than children given the same amount of time.

That last mile, getting from fluent to native-like, is statistically more difficult, as this paper shows, but like any good 80/20 rule, the first 80% of the results takes 20% of the time.

“What is remarkable about language is that we are (nearly) all extremely good at it, including adult learners.” — from A Critical Period

You can become fluent in a language in a few years of work, I see it all the time. This paper further proves that even starting much later in life, it’s still possible (if not as common) to reach incredibly high levels of mastery.

This post originally appeared on Medium.com

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63756232/acastro_181017_1777_brain_ai_0001.0.jpg)